New England cuisine isn’t making a miraculous return to its regional roots — it’s uncovering what’s been there all along.

Will Gilson has been tasked with choosing his top picks from a vastly meandering collection of New England cookbooks, some new and some not-so-new, that watch over the proceedings from a shelf above the bar.

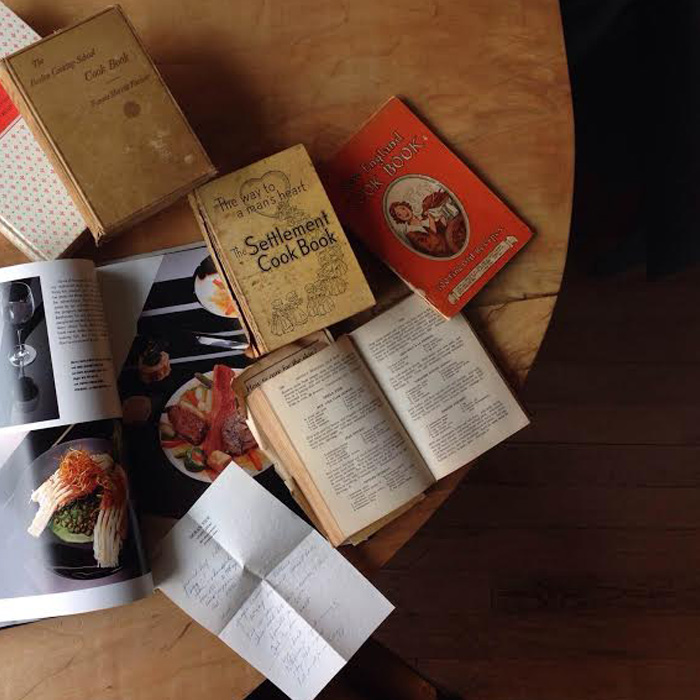

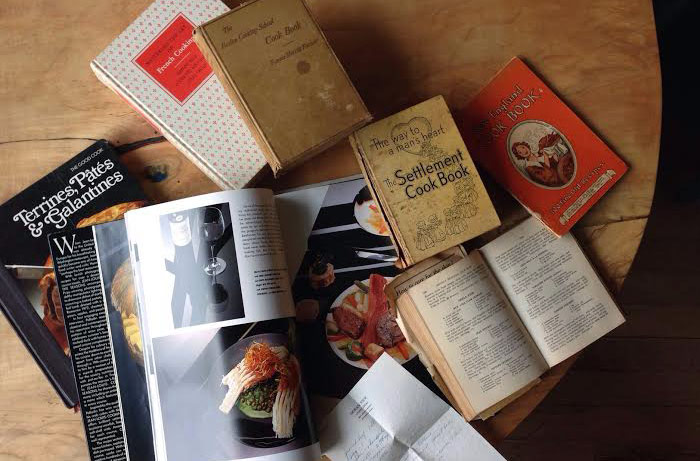

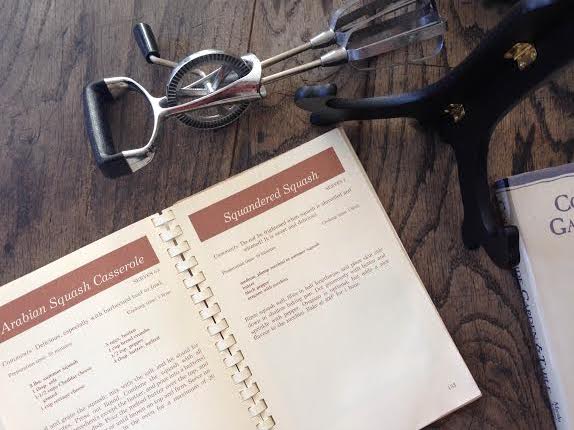

He takes his time, pursing his lips a little while he considers, then comes back with a towering pile and proceeds to spread them across a corner table by the window.

Gilson, chef-owner of Cambridge’s year-old Puritan & Company, has become the de-facto representative of New England cuisine’s foray into modern times. This development was not necessarily intentional, as Gilson will assure you, but somewhere along the line from conception to opening, the 1920s stove (now serving as a host stand) he learned to cook on, and the building’s long and storied history became just as imperative to mention as the menu. It was as if, after tales of his impressive Massachusetts lineage began to leak out, a light was flicked on for the dining public: modern New England! A return to our roots!

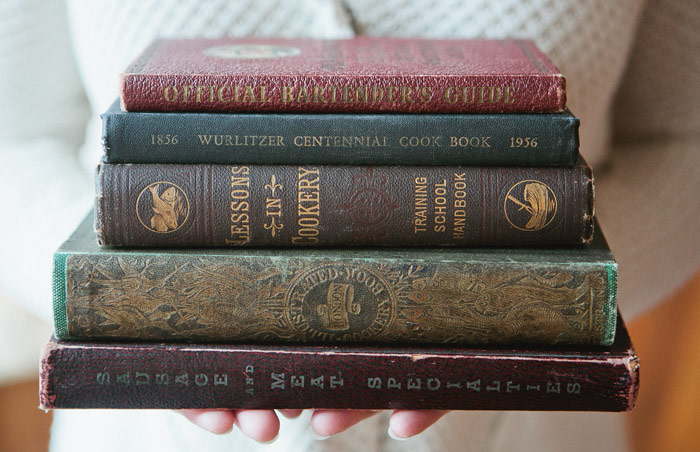

The ironic thing that one realizes when eating Gilson’s food or asking him to define such a thing as “modern New England,” is that it is less about transcribing every aspect of this area’s food memories into a restaurant setting, and more about reinvigorating the way we consider our culinary identity in general. For Gilson, the path to illuminating the true soul of New England cookery comes via a cache of old-school — think 1800s old-school — cookbooks.

“For me, these cookbooks are brain exercises. It’s not so much look at a recipe and copy it verbatim, or look at a recipe and figure out how to make it modern, it’s a way to stimulate the thought process,” he says. Their covers are worn and kitschy, remnants of a time when people probably didn’t worry so much about what their cuisine really meant in the grand scheme of things. “When I flip through a lot of these books, I try to see the things that became a foundation for New England cuisine. What are the elements that make the food that we grew up on, that people from this region are known for?”

Preservation, pickling, and curing meat, he points out, are not just all the rage with any chef worth their salt, they are techniques that kept settlers in this area alive for generations.

“It’s really inspiring to see someone like [Husk chef] Sean Brock champion the South, and be able to say, ‘This is our heritage, this is what we came up with,’” he says. “New England always has things that feel more like a joke, like we’re just up here eating chowder and lobster rolls.”

Gilson’s first experiences with quintessential New England dishes were after-school meals at friends’ houses whose last names started with O’, after-church Sunday boiled dinners, and Finnan Haddie and fried clams during trips to the Cape. His childhood, much like many others’ who grew up here, was full of sturdy brown bread, hot dogs from the can, and baked beans. He neither over-glamorizes it — in the way that a “10 Best Lobster Rolls” piece is unavoidable in every major New England publication each summer — or writes off its influence on his relationship with food. It is what it is.

“If I’m going to put Finnan Haddie on the menu, I’m not going to do it unless I can create a version that I feel is superior to something I could copy out of a book,” he says. “At the same time, I’m not trying to be too cerebral with it and shove something down someone’s throat.”

Walking the line between being too cerebral and too casual seems to be his main concern at Puritan & Company, where he strives to bring about the occasional hint of nostalgia without inciting riots around authenticity.

“What I’d like to see is the people that live here excited by the dishes that they grew up on,” he says, gingerly turning the pages of a copy of the Boston Cooking School cookbook, by Fannie Merritt Farmer. A few handwritten notes in spidery cursive from the previous owners are tucked here and there as bookmarks. “And, that people from outside New England start realizing that this isn’t just the five states of fried seafood.”

On the other side of the river, the early afternoon sun is slanting through the windows of the South End’s newest culinary treasure trove, Farm & Fable. Owner Abigail Ruettgers opens a twin copy of the Merritt Farmer book, and nearly identical yellowed papers fall out — this time covered in neat, round handwriting outlining the preparation of Yorkshire pudding.

“This was a classic wedding gift back then,” she explains. “So you’ll see a lot of copies floating around. They always look so beat up because they were so frequently used.”

Photo by Brian Samuels Photography

A native of Carlisle, Massachusetts, Ruettgers’ trade is in dog-eared and lovingly tattered vintage cookbooks and antiques, many of which hail from New England. She grew up in a 350-year-old farmhouse — similar to Gilson’s historic surroundings in Groton, a few miles west — and is named for Abigail Adams, who her mother deemed feisty enough to serve as a namesake.

The Ruettgers residence has all the trappings of a revolutionary abode; seven fireplaces throughout the rooms from a pre-insulation era (including one in the kitchen that is still used to cook with) and barns on the property that were used to dry large quantities of herbs.

“That’s what makes New England a little unusual … we’re still living in these houses,” she says. “When you grow up in those surroundings you have an appreciation for it. We have a reputation for being stodgy, but I think we’re just traditional.”

Ruettgers pulls down a pocket-sized cookbook centered around berries from its spot on the display shelves. “I don’t know what billberries are,” she says, scrutinizing one of the pages, “Or barberries.” Turns out barberries are native to the Middle East and central Asia, yet another example of the ties Boston has held to the rest of the globe for centuries.

Next, she flips through a worn cookbook from the Junior League of Boston and finds a recipe for Portuguese paella, alongside one for “Squandered Squash.” (A sampling: “Do not be frightened when squash is shriveled and wizened, it’s sweet and delicious!”)

“New England cuisine has always obviously been very seasonally driven, since we have a tough climate,” she says, “So a lot of the cookbooks you find are focused on what’s available at that moment. Lots of cod, lots of apples.”

This reminds her of something she has stowed away in one of the cabinets near the vintage cocktail sets.

“It’s very regionally focused on the culinary antiques side too, which helps me understand what people were cooking based on what they invested in,” she explains as she drags a box teeming with old apple corers to the middle of the floor. “These kinds of things were expensive at that time, because of the metal and the fabrication, but it was worth it because you used it all the time. They’re a really good indication of what people were using most in their kitchens.”

“I think we now associate ‘regional cuisine’ with fresh,” she says. “We’ve come back to wanting things that are locally sourced and haven’t traveled across the country. We’re using those traditional ingredients again, which means we’re using traditional recipes again.”

“One of things that you can’t ever anticipate is what you become known for,” Gilson says, back at Puritan & Company. It’s a difficult game for him and his team to play, since New England food has never been known as delicate, light, or refreshing.

It’s the stuff of harsh winters and booming piers; rich stews, and smoked fish. “It’s not like we wanted to find a niche that no one else was filling and jump on it. It just became a way that described what we were going to do.”

“And yet, just because this is the food that defines us, it doesn’t have to be old and stuffy and bland,” he continues. “You can still create a sausage that can be served with baked beans over brown bread, but no one says you can’t make that sausage using all these incredible flavors we have access to.”

A cursory glance at his kitchen shelves is proof of those trade routes from another time: sweet chili sauce, soy, fish sauce, dashi, seaweed, pomegranate molasses, ras el hanout, and baharat. Staying true to one’s past doesn’t have to mean stunting its future.

“You have Californian cuisine on the West Coast, low-country cookin’ down in the corner, steakhouses and big restaurants in Chicago, Tex-Mex influence in Texas, but then little New England, are we just oysters and fried clams?” he asks. “Is that all we are?”

The answer — if Gilson’s shape-shifting menu, that manages to both echo and transcend his heritage, is any indication — is obviously not.

“In these old cookbooks that are so representative of a time and place in America and New England, nothing is fried. I don’t think that has to define us,” Gilson says. “It’s about balancing flavors, it’s about championing ingredients, it’s about the story, and it’s about making people feel proud to eat food from where they come from.”

Welcome to new New England.